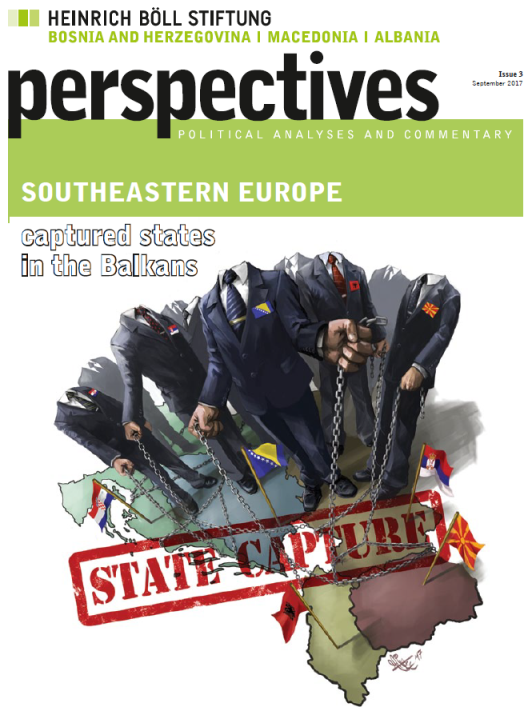

Captured states in the Western Balkans - a well-documented phenomenon.

But what are the implications for EPO governance?

In this part of the series we will begin to consider some of the wider ramifications of the latest "Balkan Affair" affecting the EPO, in particular its implications for EPO governance.

"In 2020 North Macedonia achieved a score of 35 points (out of 100) on the CPI index which put it on the bottom of the Western Balkans list together with Bosnia and Herzegovina."In 2021, Transparency International reported that North Macedonia's ranking in its Corruption Perceptions Index for 2020 was the worst result since the country's first rating in 2001.

In 2020 North Macedonia achieved a score of 35 points (out of 100) on the CPI index which put it on the bottom of the Western Balkans list together with Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The country is still only beginning to come to terms with its own recent history and the political fallout from the Gruevski era which earned it the epithet of a "captured state".

"...Mitevski chronicles and analyses the way in which the Macedonian state and society became hostage to a corrupted political elite during the years of 2006-2016."The journalist Mancho Mitevski who writes for the Macedonian daily Sloboden Pechat ("Free Press") has produced an interesting book on the subject entitled "Captured State – Understanding the Macedonian Case".

In his book - which can be accessed online here [PDF] - Mitevski chronicles and analyses the way in which the Macedonian state and society became hostage to a corrupted political elite during the years of 2006-2016.

In particular he explains how Macedonia was ruled for almost a decade by a coalition between two extremely nationalist parties, VMRO-DPMNE and DUI, each purportedly representing its own ethnic group.

"According to Mitevski, the coalition between VMRO-DPMNE and DUI was based on very strange ingredients, relations and interests."According to Mitevski, the coalition between VMRO-DPMNE and DUI was based on very strange ingredients, relations and interests. It was conducted as a "marriage of convenience" which was primarily driven by "pure interest to rule and, of course, to share the privileges of the power of government".

Mitevski explains how the VMRO-DPMNE/DUI coalition "captured the state" within a very short period of time:

"Instead of state and citizens’ interests and priorities, since the very formation of the coalition government they were more dedicated to the party priorities and the personal interests of the party elites."

Violent scenes from inside the Macedonian Parliament on "Bloody Thursday", 27 April 2017, including attacks on SDSM politicians Zoran Zaev (top centre) and Radmila Ã

ekerinska (top right).

"In the meantime, the country's ongoing lack of progress in tackling endemic corruption and ensuring adherence to the rule of law has contributed to the reluctance of the European Commission to progress with its request for EU membership."Indeed cynics might be inclined to point to the fact that the junior partner of that "marriage of convenience" - namely, the DUI - has managed to remain in government to this day, albeit with a senior coalition partner of a different ideological hue since 2017 - namely, the social-democratic SDSM.

In the meantime, the country's ongoing lack of progress in tackling endemic corruption and ensuring adherence to the rule of law has contributed to the reluctance of the European Commission to progress with its request for EU membership.

Together with five other countries of the Western Balkans – Albania, Bosnia-ââ¬â¹Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro and Serbia – North Macedonia appears to have been permanently condemned to the EU's waiting room for aspiring members.

"As Marko Kmezić of the Centre for Southeast European Studies at the University of Graz in Austria explains, these Western Balkan countries have successfully managed to construct a deceptive "democratic façade" during the three decades since the beginning of democratisation processes (which started in the late 1980s to early 1990s)."As Marko Kmezić of the Centre for Southeast European Studies at the University of Graz in Austria explains, these Western Balkan countries have successfully managed to construct a deceptive "democratic façade" during the three decades since the beginning of democratisation processes (which started in the late 1980s to early 1990s).

Everything seems fine on the surface: there are formal constitutional declarations of a separation of powers, including a strict system of checks and balances; legal acts guaranteeing freedom of expression are promulgated and elections are held.

However, behind the façade, the political elites in these states rely on informal structures, clientelism, and control of the media to manipulate weak state institutions and undermine democracy.

"However, behind the façade, the political elites in these states rely on informal structures, clientelism, and control of the media to manipulate weak state institutions and undermine democracy."Kmezić speaks of a situation in which the Western Balkan region suffers from the palpable absence of "a functional rule of law" - which is considered to be a key dimension of democratic substance.

In February 2018 (PDF here), the never-ending EU enlargement saga in this region took a new turn as the European Commission unveiled its strategy for “A credible enlargement perspective for and enhanced EU engagement with the Western Balkans”, which is referred to by EU policy wonks as the "Rule of Law Initiative"

According to Andi Hoxhaj of the School of Law at the University of Warwick in the UK:

"...the underlying message in the rule of law initiative is that the Commission plans to make use of all of the leverage provided in the accession talks frameworks for as long as possible, by delaying the Western Balkans accession to the EU in order to avoid any repetition of the scenarios of Hungary and Poland, where there were clear elements of backsliding in their commitments to the rule of law, or, in the cases of Bulgaria, Slovakia, and Malta, where high-profile politicians were observably involved in corruption and organised-crime networks."

"...the problems are not limited to the aspiring EU member states of the Western Balkans."There are plenty of examples of states which managed to obtain a clean bill of health prior to being granted EU membership, but which have failed to maintain their commitments to the rule of law and the fight against corruption following accession.

An article by Anja Vladisavljevic, a journalist associated with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN), published in February 2020, discusses how Croatia is perceived to be "backsliding" on corruption following its EU accession in 2013.

The article reports that perceptions of corruption in Croatia have slumped to their worst level in five years.

One of the explanations given is that Croatian politicians no longer face the outside pressures which they did during the period when the country was trying to qualify for EU membership.

“Since joining the EU, Croatia has regressed in the fight against corruption,” said Oriana Ivkovic Novokmet, executive director of GONG, a civil society group that promotes good governance, rule of law and human rights.

“There is no external pressure to encourage change; the [European] Commission, for example, has abolished the anti-corruption reports it once had.”

Responsibility for the fight, Ivkovic Novokmet said, had fallen on institutions now firmly in the hands of the conservative Croatian Democratic Union, HDZ, in power since January 2016.

“The few remaining independent institutions are systematically undermined by the government,” she told BIRN.

"In the next part we will consider the extent to which “captured states” might contribute to the risk of “captured delegates” on the governing bodies of international organisations, such as the EPO’s Administrative Council."In the absence of a mature and robust rule of law tradition, the risk of ending up as a "captured state" remains, especially if external monitoring pressures are relaxed too soon.

In the next part we will consider the extent to which "captured states" might contribute to the risk of "captured delegates" on the governing bodies of international organisations, such as the EPO's Administrative Council. ⬆