"Modernizing" as in adding vendor lock-in and pushing proprietary dependencies

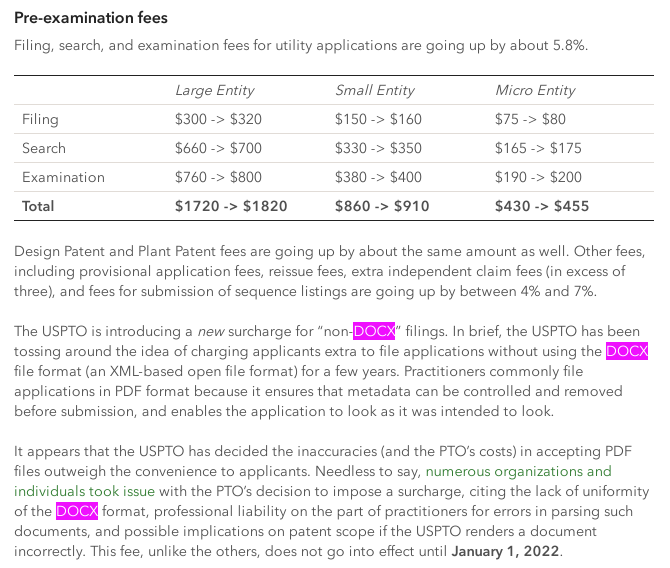

There are still a few months to fix this, but for now the US Patent and Trademark Office's (USPTO) Acting Commissioner for Patents, Andrew Faile, and Chief Information Officer, Jamie Holcombe, have announced that starting January 1st, 2022, the USPTO will institute a surcharge for applicants that are not locked into Microsoft products via the proprietary DOCX format. From that date onwards, the USPTO will move away from PDF and require all filers to use that proprietary format or face an arbitrary surcharge when filing.

First, we delayed the effective date for the non-DOCX surcharge fee to January 1, 2022, to provide more time for applicants to transition to this new process, and for the USPTO to continue our outreach efforts and address customer concerns. We've also made office actions available in DOCX and XML formats and further enhanced DOCX features, including accepting DOCX for drawings in addition to the specification, claims, and abstract for certain applications.

One out of several major problems with the plans is that DOCX is a proprietary format. There are several variants of DOCX and each of them are really only supported by a single company's products. Some other products have had progress in beginning to reverse engineering it, but are hindered by the lack of documentation. DOCX is a competitor to the fully-documented, open standard OpenDocument Format, also known as ISO/IEC 26300.

DOCX is not to be confused with OOXML, though it often is. While OOXML, also known as ISO/IEC 29500, is technically standardized, it is incompletely documented and only vaguely related to DOCX. The DOCX format itself is neither fully documented nor standard. So the USPTO is also engaged in spreading disinformation by asserting that it is.

Previously:

(2015) Microsoft Threatened the UK Over Open Standards

Documents submitted to the US Patent and Trademark Office should be in .DOCX format starting from next year – and if you want to stick to PDFs, that will cost extra.

“At the USPTO, we are continuously working to modernize and streamline our patent application systems,” the agency announced this week. “To improve application quality and efficiency, the USPTO will be transitioning to DOCX for all filers on January 1, 2022.”

The office said it decided to make the change years ago in an attempt to streamline the patent examining process. DOCX, otherwise known as Office Open XML, is standardized as ECMA-376 and ISO/IEC 29500. Though it was created by Microsoft for its own products, such as Word, the file format is supported by LibreOffice, OpenOffice, Google Docs, and others. And though the Windows giant has sworn it won't sue over licensing and patents regarding DOCX, there are some caveats.

Until now, it has been optional for a practitioner to file a US patent application in DOCX format rather than in PDF format. But USPTO now proposes to charge a $400 penalty for filing a patent application in non-DOCX format. This is a very bad idea, for reasons that I will discuss in detail. Only if USPTO were to make fundamental changes in its way of receiving DOCX files would it be acceptable for USPTO to impose a penalty for filing in a non-DOCX format.

USPTO needs to follow WIPO’s example, permitting the practitioner to file a “pre-conversion format” version of a patent application along with the DOCX file. In the event of some later problem with USPTO’s rendering of the DOCX file, the practitioner would be permitted to point to the pre-conversion format, which would control in the event of any discrepancy.

The normal way to file US patent applications is in PDF format. With PDF format, the applicant has complete control over the appearance of characters and symbols.

Some years ago, the USPTO began beta-testing a system that would permit a practitioner to file a patent application in DOCX format instead of in PDF format. Yours truly was among the very first of the beta-testers of USPTO’s system for DOCX filings. As implemented by the USPTO, the practitioner would upload a DOCX file, and USPTO would render the DOCX file in a human-readable PDF image format. As part of the e-filing process, the practitioner was expected to proofread the rendered image as provided by the USPTO’s e-filing system. The notion was that the practitioner would be obliged to catch any instances of USPTO’s system rendering the DOCX file differently from the way the practitioner’s word processor had rendered that same DOCX file. If, for example, some math equation or chemical formula had gotten corrupted in USPTO’s system, the practitioner would expected to catch this prior to clicking “submit”.