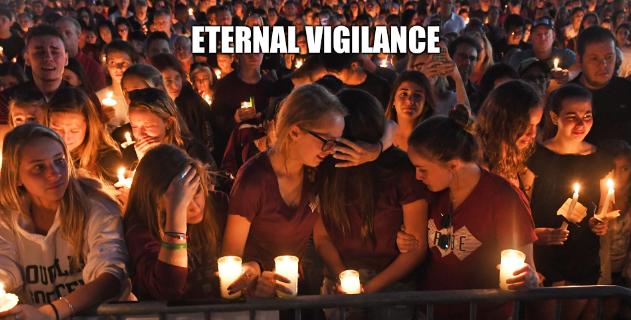

THE one thing one comes to realise after decades of antiwar or environmental activism is that it's an "eternal vigilance" thing (to reuse Founding Fathers' words of caution); it never really ends because when one threat is removed/tackled/mitigated several others come to replace it; the "others" can be either different brands or different strands (one might say modalities, paradigms) of threat. To use an example, one can hope for the bankruptcy of Shell, only to find Chevron replacing it. Or one can hope for the end of fossil fuels, only to discover threats associated with nuclear energy as a substitute. In the case of war, we all know that Biden's record on militarism isn't giving much hope for peace activism; he may not be as bad as his (soon) predecessor, but the antiwar movement isn't disillusioned and it'll carry on fighting for another 4 years.

"A lot of people believed that "Linux everywhere" means "world domination" or something, but in practice Linux in every pocket (Android) means Google dominates the world."Now, on to software...

The history of software is relatively short, assuming we mean computer software and not prototypical operations/steps one carries out manually (a human operator). The latter predates machines.

When computers got started (or just "machines" as many were known as back then) programming them was not easy. The first programmable computer was made right here, so computer programs could be loaded into 'general-purpose' machines and then complete some task. The underlying code would run on the few such machines which existed at the time. Over time more and more machines (with lower price tags) would be able to load and run such programs. Later on copyright laws, not just something like trade secrets, would restrict the sharing of such code and GNU was born to turn copyright law against itself (or on its head), keeping those who wanted to share code capable of imposing reciprocity.

Over the next few decades we'd come to discover DRM, TiVoization and other technical means -- putting aside legal means (e.g. DMCA, CFAA) -- for restriction on sharing. Not just of code...

Then there's the aspect of software patenting, which complicates sharing of programs that aren't even identical to some prototype (sometimes merely hypothetical).

The main point is, over time the goalposts move; companies lobby and buy laws, typically in order to enrich themselves and forbid competition. The brands may change over time. In the old days IBM was eager to stifle competition, then came Apple and Microsoft... nowadays there's much more in the mix.

Does that mean defeat is inevitable? No, not necessarily. If there were no green activists, the world would be a vastly more polluted place. If fierce antiwar protests didn't take place, politicians would start more wars than they currently do. In the case of software, users' demands can prevent or at least slow down erosion of human rights in the digital domain. Privacy, free speech and many other aspects to it...

Does that mean defeat is inevitable? No, not necessarily. If there were no green activists, the world would be a vastly more polluted place. If fierce antiwar protests didn't take place, politicians would start more wars than they currently do. In the case of software, users' demands can prevent or at least slow down erosion of human rights in the digital domain. Privacy, free speech and many other aspects to it...

Perhaps more importantly, framing the issue in some particular way and then tackling this issue would not guarantee other (new) issue won't crop up, emerging out of nowhere. Many people thought GitHub was mostly benign and even symbiotic ('free' hosting) until Microsoft bought it. A lot of people believed that "Linux everywhere" means "world domination" or something, but in practice Linux in every pocket (Android) means Google dominates the world. More than 15 years ago I habitually referred to Google as "GNUgle" (a joke) because almost all of its underlying infrastructure ran GNU; years later it became more apparent that Google was antithetical in a lot of ways not only to GNU but also to the GPL (which it now opposes). History teaches society that corporations aren't our friends but at best temporarily our allies and the bigger they get, the less ideology they have (founders leave) and the more they rely on greedy shareholders.

Software freedom isn't really profitable; profit isn't the goal. To the users it means cost savings (especially in the long run), but only because Free software lessens their dependence on few greedy corporations that manipulate them for financial gain.

Richard Stallman has fought for software freedom for nearly 40 years (earlier this year we shared an old video of him, dated early eighties); he's still active, but he's a tad shy to say controversial things, seeing what backstabbers in GNU (many IBM employees) are poised to do to him. Last year's "cancel culture" drama/trauma made him a vastly more apprehensive and thus "moderate" advocate, i.e. not necessarily as effective as he was before. He turns 68 in spring (3 months from now) and more people need to carry on fighting, securing and extending his legacy. It's not as if we need "x more years" to "win"; the battle will be an eternal one -- or as eternal as software itself will be. Don't join the "fight" for a quick and satisfiable "win"; saddle in, pick a keyboard, choose a billboard and get ready for a lifelong war. What constitutes a win is any time malicious forces withdraw or "change their mind" (due to backlash). "Many people can only keep on fighting when they expect to win," Richard Stallman once said. "I'm not like that, I always expect to lose. I fight anyway, and sometimes I win." ⬆

Photo credit: Pratheesh Prakash at Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Chennai; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported