The Privacy Shield was derided by its critics as "lipstick on a pig"

As we saw in the last part, following the invalidation of the Safe Harbour by the CJEU in its "Schrems I" judgment a revised framework for regulating transatlantic exchanges of personal data was pulled out of the hat in the form of the Privacy Shield.

"The hurried manner in which the Privacy Shield was cobbled together meant that it always smacked of being a flaky and legally unsound last minute political compromise between the EU and the Obama Administration."The first signs that the revised arrangement might not last very long came in January 2017 during the early days of the Trump Administration when the incoming POTUS signed off on a new Executive Order on "Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the U.S."

Among other elements, this Executive Order directed US government agencies to “ensure that their privacy policies exclude persons who are not United States citizens or lawful permanent residents from the protections of the Privacy Act regarding personally identifiable information".

This prompted certain commentators, such as MEP Jan-Philipp Albrecht, to express concerns about the tenability of the Privacy Shield and to call for its suspension pending clarification of the legal implications of Trump's Executive Order.

The European Commission was quick to dismiss these concerns.

Others who remained sceptical about the tenability of the Privacy Shield arrangement confidently - and accurately - predicted that its days were numbered.

"The Schrems II judgment has significant implications for "cloud computing" services."The final nail in the coffin came in 16 July 2020 when the CJEU delivered its judgment in the case of Facebook Ireland Ltd. v. Maximillian Schrems – known as "Schrems II" – which not only invalidated the Privacy Shield agreement but also put other data transfer mechanisms into significant doubt.

The CJEU found that due to the possibility of access to personal data of EU citizens by US authorities, the Privacy Shield infringed EU data protection regulations because it did not provide adequate GDPRââ¬âcompliant protection of personal data.

The Schrems II judgment has significant implications for "cloud computing" services

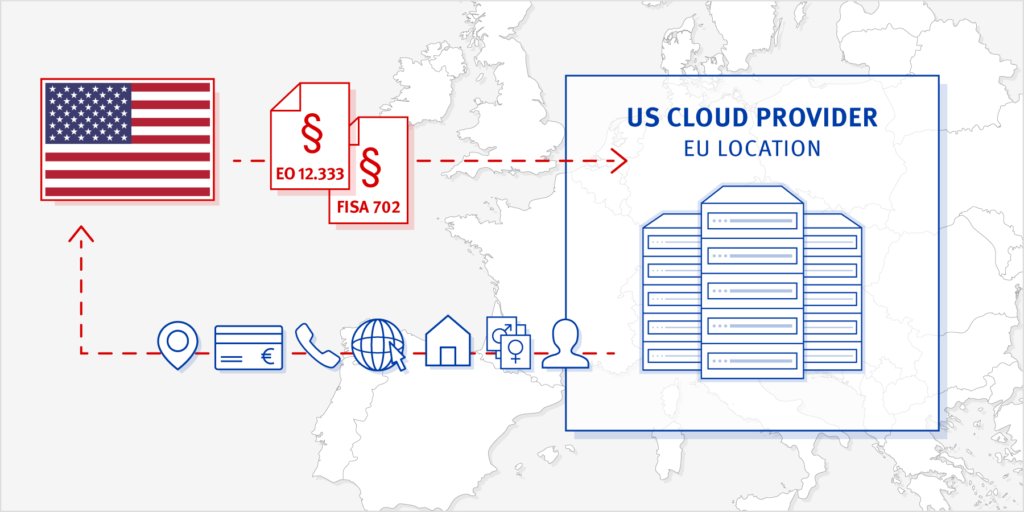

"The majority of cloud services are provided by vendors located in the US. The servers for the purchased services are partly located in the US, partly in Europe."Merely relocating the data to an EU-based region in these clouds is not sufficient, because the problem is not geographical in nature.

The decisive issue here is that US-owned cloud vendors are subject to US jurisdiction and US legislation can be used to them to hand out customer data to the US government, even if the servers storing that data happen to be located on foreign soil.

Even if a server is located in the EU, US authorities may access the stored data via FISA (Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act) 702 and the EO (Executive Order) 12.333 which apply to all Electronic Communication Service Providers headquartered in the US.

"In December 2020 it was reported that the Swedish data protection authority had imposed the first GDPR-based fine for lack of adequate protection of sensitive data stored in a USââ¬âbased cloud platform after the Schrems II decision."In that case the UmeÃÂ¥ University in Sweden was fined SEK 550,000 (approx. € 54,000) because it was found to have processed special categories of personal data concerning sexual life and health using storage in a cloud service of a US-based provider, without sufficiently protecting the relevant data.

The Swedish data protection authority referred to the Schrems II judgment and took the stance that per se a data transfer to the US triggers a high risk for personal data because data subjects are limited in protecting and enforcing their privacy rights.

In the next part we take a further look at the fallout from Schrems II in Europe and how the judgment has given new impetus to the discussion about European "data sovereignty". ⬆