Reference: Finite-state machine

Reference: Finite-state machine

THE notion (or rationale) of software patents is based on the misguided idea that rather than let people acquire a monopoly on a particular implementation using a particular computer language we should give people a monopoly on some vague series of instructions (very broad, not even pseudo-code), irrespective of implementation details, and that this way developers would have a greater incentive to write more code and better code. In practice, however, people who write computer programs already have a sort of monopoly on their own implementation because when they write code it is automatically copyrighted and unless the underlying code is hidden away in binary form, it is not so incredibly hard to enforce these monopoly rights. When it comes to patents, the monopoly's scope is so broad (and the covered idea is so vague) that virtually any computer program, even if developed independently (neither mimicking anything nor relying on patent surveys), is infringing. For instance, a computer program with something resembling an hourglass can be deemed infringing, no matter the visualisation of the time indicator, e.g. progress bar (or equivalent). Developers thus need to start worrying about any such mechanism which is indicative of progress/latency.

“A human undertaking the task of sorting book on a shelf alphabetically by title knows that she is dealing with books, that the sequence of words on the binding are titles, and that words are composed of letters, and so forth.”

--Robert SachsSpeaking of software patents, Robert Sachs of Bilski Blog has just released the next (third) part of his long paper about software patents being metaphors (abstract) and he notes: "Another key difference between how computers perform their operations and how humans do is that humans, but not computers, understand what they are doing, and the meaning of their operations. A human undertaking the task of sorting book on a shelf alphabetically by title knows that she is dealing with books, that the sequence of words on the binding are titles, and that words are composed of letters, and so forth. She performs these operations directly on the words. This knowledge of the domain impacts how the operations themselves are performed. A computer can sort the same titles, but only once each title is represented as a string of numbers—the computer does not “know” that the numbers represent a book title any more than the human’s finger “knows” she is moving a book, and cannot use this knowledge to change the manner of sorting."

Sorting algorithms are classic logical operations that are typically taught in the first year of computer science courses. Should they too be patentable? Where does it end? They don't even do anything that wasn't already done before (by humans, by hand). The fourth part of the series, published earlier today, cites the Benson case and states: "The court offers two further insightful observations. First, “Pencil-and-paper analysis can mislead courts into ignoring a key fact: although a computer performs the same math as a human, a human cannot always achieve the same results as a computer.”"

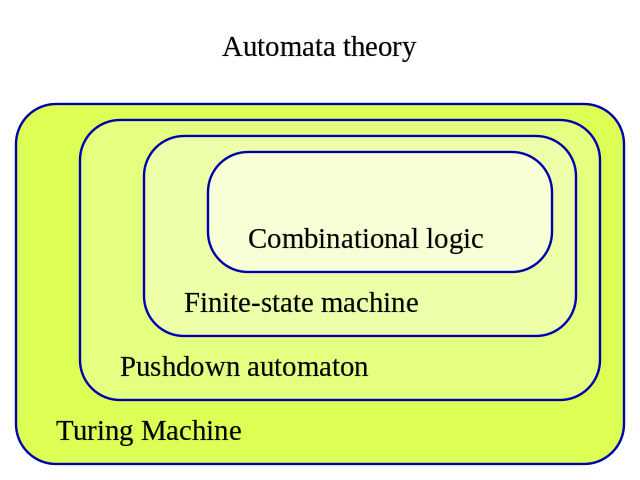

"These are all reducible to a Turing machine and every pertinent operation can be carried out by a human rather than a processor, no matter the complexity (e.g. number of bits in the 'pipe')."The paragraph goes on with quotes like that, but it does not change the fact that any computation carried out by a computer can also be done on paper (it's just a question of how long it takes for the human operator to do so). These are all reducible to a Turing machine and every pertinent operation can be carried out by a human rather than a processor, no matter the complexity (e.g. number of bits in the 'pipe').

There is still one more part (the finale) to come from Mr. Sachs. It's part of a long paper on the subject of software patents (not a paper from software patents lobbyists like David Kappos, now funded by Microsoft and others to shame and pressure the system). ⬆