Technology: rights or responsibilities? - Part VI

By Dr. Andy Farnell

Back to Part I

Back to Part II

Back to Part III

Back to Part IV

Back to Part V

Rights and markets

What are "markets"? There are two competing theories of markets. One is that free markets are the ultimate realisation of the will of the people, whose expressed demand is the principal driver. Another take is that markets are actually driven by supply; and in the case of technology by a narrative of "determinism" or "design". The suppliers decide what is available to the people, which is often counter to their democratic will but meets profitable expedience and efficiency.

Interestingly, although we still use the word "capitalist" to describe (and complain about) our way of life, the reality is much closer to the Communist era ideologies of central planning. It is a result of the many conceits of commercial "data science" (some of which are fraudulent or at least largely ineffective) which fail to account for the limitations of market information and place ideological preference for "efficiency" and central control above pragmatic human relations.

Whereas Adam Smith was correct that the demand for bread was in proportion to the hunger of the population, the idea that "market demand defines technology" has always been suspect. Digital technology does not work that way, being both a product in and itself the infrastructure that defines markets. Digital tech is thus a push process where technical possibility determines products that are aggressively marketed (sometimes before they really exist) and then selected by Darwinian "stickiness" or sheer luck. A key factor here is influence (AKA advertising) and strategy within large and opaque organisations.

Another key factor is political ideology of governments, and specifically the conceit of a "Digital State", an apparatus far beyond the basic legibility necessary for governance. The early 21st century is defined by an alignment, an unholy alliance, between state and markets, which have converged in the post-Reagan/Thatcher era. It is not the "military industrial complex" of which Eisenhower warned, but a far more intricate and all-consuming "data industrial complex" which extends Weber's bureaucracy to Kafkaesque proportions. Other than absorbing a defence budget the military could be relied on to make trouble in someone elses' country. Data gangsters turn their weapons inward, at our own population - of course always with kind words and good intentions to "help people", to make "a better society" and moreover an "efficient and profitable one".

Actual "demand" plays a vanishingly small part in all this, mostly because end-users do not know enough about what's possible to make cogent requests. Also since technology does not actually solve problems but merely displaces labour into a new realm, most of us are quite ambivalent about solutionist tech. Now we work more hours than ever in history to do intangible things that make no sense.

People acquire technology by social osmosis, by seeing other people using it and enjoying utility. Or having it forced upon them. Early adopters and technophiles are a minority with a disproportionately loud voice. They are amplified and easily leveraged by appealing to their sense of insecurity at "being left behind". They help tech to become the lens through which we see society, as a commercial technological concern with an interest in promoting itself. Most of this is covered by Lewis Mumford and Neil Postman in their very good analyses.

Ever since travelling hucksters peddled coloured water as medicine a section of people have taken on-trust things they do not understand. Likewise, in a digital society, citizens may have skin in the game but lack the necessary stake of capacity. For example, most of us have no interest in how electronic voting machines work, whether they are remotely programmable, whether they store votes in secure memory or transmit data with encryption and authentication. But we do care a lot about whether elections are rigged.

But these two positions are incompatible. One does not get to have any of the alleged benefits of digital systems (there are many along with attendant risks), without a commitment to understanding. People understand a box and a piece of paper. Being a knowledge stakeholder with the capacity to decide is the basis for all social contracts that require trust. They need informed assent.

Since education is expensive, time consuming and effectively reaches only a minority, it is simpler for governments to foist technologies on people. One of the effective ways to do this is to make a show of delegating technology to priviate enterprise and allow fake "market" forces of "efficiency" do the dirty work. Therefore in all places where we see electronic voting machines deployed it is absolutely not because the citizens asked for them. It's because someone with a tech company close to an influential politician struck a deal to supply this new "need".

Even when advertising was informational, motor cars and radios were beyond most people's comprehension. We've relied on governments to set boundaries and educators to fortify people. We've also relied on citizen experts, hobbyists, amateur scientists, teachers, youth leaders, and honest journalists to provide a network of checks and balances on electronic technology.

But what happens when governments do not themselves understand the wares they hope to regulate? What happens when the education system becomes a jazz-handed squee of gushing exuberance for tech that wiser minds would urge caution toward? What happens when informal recommendation and networks of peer expertise are replaced by highly paid "influencers" who simulate organic chatter?

Few things are quite as opaque and mysterious as digital technology. Our low capacity for accurate value judgements about it turns legible products into cargo-cult items. Having half the world superstitiously doting on technology they see as "magic" is not sustainable. For one thing, it means all standards are a race to the bottom. As the quality of everything spirals the drain of enshitification and AI slop, digital technology becomes a market for lemons in which the cost of everything tends to zero and its value to even less.

Governments are hard pressed to regulate supply or functionality, and mainly do so on behalf of their industry lobbyists rather than the people. They are constantly at risk of regulator capture and under pressure to become vassal to outside "investment". Meanwhile, companies cannot change their internal paradigms thus humane and saner technology never rises above the noise floor of the lowest common denominator of consumer tat for short-term markets.

People basically buy what they're told to, or what they feel they must. Therefore, to avoid a race to the bottom of quality, we have to ensure special technology rights and strategies regarding; accuracy of advertising, safety, long-term resilience, transparency, freedom of information, open source, free discussion, ownership of cryptographic keys and reverse engineering.

People have fundamental property and trade rights to take control of and understand the technology they own, examine and repair it, modify and resell it, and to enjoy a competitive market where they can genuinely select and buy in good faith using clear information. Practically everything bigtech does is against this and works to erode those rights.

In the US organisations like American National Standards Institute (ANSI), International Standards Organisation (ISO) have led technology standards, but like Europe's CEN and the UK's Trading Standards these are weak "advisory" groups without mandate to define essential requirements beyond basic safety. Most of the serious digital harms we can identify in 2025 are not even incidentally touched by their remit. Organisations like the World Trade Organisation (WTO) are entirely about the rights of manufacturers and sellers, and are frequently against the interests of "consumers".

Vendors, on the other hand, love black boxes, hidden functionality, logic bombs, dead-man's switches, forced updates containing mystery changes, encrypted "updates" that phone home, degrade functionality, delete files or install back-doors. It's breathtaking to see how hostile tech has gotten toward us.

Some vendors work hard to conceal what their products do. In the now famous VW emissions scandal the car manufacturer programmed their products to act deceptively, performing differently depending whether they were being audited or used normally. And what does any product really do? Only what it's last software update tells it to. Devices which speciously connect to the Internet are a menace to public rights, privacy, security and safety.

It's fairly common for products like HP printers or Amazon eBook readers to be basically vandalised over the internet by the companies that sell them. Let's note as an aside that if individual "hackers" had performed these deeds they would face decades in jail under exceedingly harsh laws - yet companies are given a hall-pass to wreak misery and financial loss. A subject in cybersecurity called "vendor malware" - where the attacker is actually the manufacturer or OEM retailer - deals with these threats that are less well known to the public.

Exposing such tricks, and protecting the very possibility of exposure, remains the domain of consumer rights groups and investigative 'hacktivists' and artists. So naturally, vendors also love to silence these critics, sow disinformation, smear detractors, and spread fear, uncertainty and doubt (FUD). To this end they abuse copyright, patent and trademark laws, and amplify public fear about safety.

Many tech companies make a PR show of "standing-up for customers privacy rights". Secretly, where it buys them favour they align with draconian elements in government to lend tepid support to unworkable ideas like back-doors in chat software, because any attack on the sovereign property rights of technology owners is in their interest. There are good arguments that Bigtech actually loves regulation since it can steer the rules to work for itself. They can afford to pay huge fines. Regulation tends to harm smaller competitors and create barriers to entering markets. The end goal seems to be to strip citizens of any property rights in the devices and systems necessary for interaction so that participation in a digital society is something rented by the hour.

Lastly, big tech companies work hard to undermine alternatives. Obviously they take technical steps to break code and protocols to lock out competitors and make their wares deliberately incompatible with competing products. Everyone understands the "lock-in" nature of commercial tech by now. But companies also spend a fortune on information warfare.

You're likely reading this through a less well known channel because thoughtful (if I may be so immodest) tech-critique is not the sort of thing you print on your platform if you want to keep that Bigtech sponsorship flowing. To read the mainstream media one would think that Microsoft and Google are the only two companies on the planet right now. That's a lot of paid-off journalists. Other activities include press hit pieces against free software and smaller competitors. Lately we've seen campaigns of "AI" generated slop and spam to spread untrue claims about security weaknesses in alternatives and to wage personal hate and smear campaigns.

Markets regulate valuable goods. In a hyper-individualist world of all against all, markets have nothing to say about regulating valuable harms. But an arms race of devices weaponised against their end users has emerged. Consequently, markets have quite failed to champion technical security - which explains the present cybersecurity crisis,

We've reached a stage where the behaviour of tech companies is so delinquent and government regulation is so depressingly weak that a situation of political struggle like that of the 1960s is emerging. What we're seeing more is that the product is the malware and the vendor is the threat. People are feeling the pain, seeing the cracks and getting desperate for alternatives.

There is no simple historical precedent. Although incidents like Crowdstrike and Solar-Winds are costly and embarrassing we don't experience them as grand engineering disasters like the Titanic or Hindenburg which create a spectacle and change the course of industry. It's just business as usual the next day. Undoubtedly lives are lost in massive tech outages, and the costs are immense. But harm is distributed amongst millions of victims.

Nor do we experience degenerate tech quality the same way as Tylenol, Bextra or any of the classic food and medicine product recalls. There is nothing to "recall" with software which is just overwritten with the next iteration. Perhaps the closest analogy to the present software crisis is tobacco, as Bigtech works so hard to cover-up and normalise harms. The argument of the vendors is that people are happy with shitty, invasive and abusive technology. They keep buying it, so what's the problem? The market has spoken! In many ways they are right. Perhaps we get the technology we deserve, but something seems missing in that worldview.

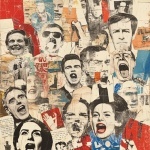

Maybe we're thinking about this all wrong. I keep talking about digital as if it were a product. But it seems hard to explain a phenomenon where we have just two massive power centres, two operating systems, two main browsers both of which do more or less the same thing but are abusive and crappy, and the people responsible keep getting away with it and face no consequences. Where have we seen this situation before? Political parties!

Perhaps we should pay more attention to this similarity? Isn't "politics" also a quasi-market? A market of ideas? Isn't it also one that has fallen into disrepair and now seems to have nothing to offer except childish mud-slinging and lower-primate behaviours?

It's not just because tech companies and their leaders imagine themselves usurping legitimate political power and making their products a form of governance, but because of the uncanny parallel bankruptcy of genuine creative ideas. Tech is stuck in the same way that politics is stuck. It's fallen into a local minima from which it cannot escape.

So, as with political parties, even if people want high quality alternatives in digital tech, after almost 40 years of complete dereliction and cowardice from governments to maintain a competitive tech economy, they have few places to turn. Where is the law? Where is political courage? This leaves only direct action, boycott, protest and creative civil disobedience as the tools for change. Mums are learning to hack, not to become cybercriminals, but to take back control over their kids phones.

As parents finally start to take direct control of their kids consumption of technology (perhaps many will argue "as they long-ago should") the sentiment we have yet to negotiate is not "Think of the children" but "Think of the ADULTS!". We have not yet sincerely admitted that we all need protection from a free market in abusive digital technologies. Nor have we learned to assert our rights to reject technology that is a risk to us and which we neither need nor want.

And who will step up to counter the new challenges of threats to digital sovereignty? The NSA? The FBI? The NCSC? The European Commission? NATO? Your Mom? Or will we need to form new civil institutions to defend civic cybersecurity and make sure that our digital society is one that we the people define and create with a democratic mandate? Existing "markets" are a sorry and weak guide for technology, because they are not genuine - but to the extent we can see the urgency for real markets, ones that respond to demand and encourage new blood, we should work to create them. That will require us all to be a lot more active.