Technology: rights or responsibilities? - Part VII

By Dr. Andy Farnell

Back to Part I

Back to Part II

Back to Part III

Back to Part IV

Back to Part V

Back to Part VI

Deeper roots of technological strife

We're on a journey to explore rights, responsibilities and technology in this fix-up series, and in the next part we're going to move on to analyse the idea of responsibilities in a chapter that is still taking shape with a little input from Dr. Richard Stallman.

We would not be asking these difficult questions if there were not an unease or problem in the air. What is the deep problem that has "gone wrong" with our technology that a reappraisal of responsibility might help to repair?

In the last part we examined why technology is not, and never has been, a neutral pursuit for dispassionate scientists and engineers just trying to make the world better. That idea owes more to what rationalism borrowed from the Crusades. It is a "spreading of the word by fire and the sword". The idea of "a right way of doing things". A 'right' way of being. Postmodernism questioned that. Threatened and upset by this, authoritarianism snapped back with a vengeance.

Systems that learn, humans, neural networks, and institutions, have an unfortunate failure mode in which preference becomes habit, habit becomes truth and "truth" becomes a prison that prevents any new thoughts and growth from emerging. We get stuck on a local minima for improvement and start saying really silly things like "history has ended", because we lack imagination of the future. To twist the words of Einstein and Peter Deutsch; to know is human, to imagine is divine. And imagination is much, much more than hallucinating from a soup of prior experience.

In our stuckness, a possibility once becomes a necessity forever. We ossify. Our minds grow from something like a sapling with immense suppleness and flexibility into a solid tree, brittle and set in its ways. A tree that will snap in the wind. It's why we need a young generation to come along and prune-back what we've built every so often. However, our youth are presently stuck, frozen in fear and contradiction.

Last week more than half of Americans voted in a government which is the very model of entrenched contradiction. It claims to champion everyman interests against patrician institutional power, but its new high-priests of the techno-religious order, who promise a Utopian "singularity", deliver only division, alienation and unemployment. A coalition of entertainment and propaganda moguls like Bezos, Zuckerberg, and Musk are more obdurate to popular voices than the simulation of democracy they intend to sweep away.

That outcome was surely a feat of technological propaganda by corporate-owned social control media from which people are now turning away in disgust. But Media outlets like the Guardian seem a little late and a more than a little hypocritical in shunning emerging US technofascism and the use of communications technology to foment violence and turmoil. Since 2014, with the appointment of ex-Google David Gehring and Rachel White to help "build Silicon Valley relationships" and a Digital News Initiative, The Guardian have cheered on the shenanigans of Meta, Apple, Microsoft and every other tech-giant stealing the lunch of journalists and creatives. Boycotting 'X' now, seems a desperate and empty gesture.

To my mind, all of this misuse of communicaton technology amounts to a debasement of science. Einstein had a question that I always found more interesting than General Relativity; whether humans can survive technology?

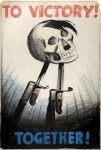

Science in the untainted hands of a child has infinite curiosity. In the hands of an adult, wracked by fear of mortality and shame, it becomes a "civilising force" through which nature can be brought under control and "other-thinking" primitives and savages must be "brought up to date" and thus "saved". It becomes technofascism, poetically described here.

Truth, whether obtained from prophets, books or particle accelerators has always had a certain, shall we say "righteous totalising" tendency. Being Right; the STEM academic's disease that affects us as climate and technology activists as much as it affects greedy industrialists, is seductive. That's something Heidegger understood but admitted was so powerful a path he could not save himself from his fate as a regretful Nazi sympathiser. It sucks you in, knowledge, power and a sense of riding a wave of 'progress' in some 'great historical moment'.

We become part of the "chosen ones" and suffer tunnel vision that blinds our peripheral senses, making us less tolerant and less compassionate. People must "get with modernity" or be ridiculed, marginalised, and eventually if not "cooperative", eliminated. In the current formulation, those who willingly surrender their privacy, dignity and autonomy to the New Digital Fatherland are superior and 'modern'. They "accept the new reality". They are "harmonised". However, most of us with our mouths shut are just pretending to hum along in the choir. Those quiet, obedient, "Good Germans" will not rock the boat of Volksgemeinschaft realised in the happy-clappy cult of social-control media and ubiquitous "convenience".

As scientists we built telescopes to gaze at the infinity of the universe and microscopes to see the smallest things. There is a common-sense idea that using instruments to measure things reveals more of the universe and so expands our vision. But the philosopher Husserl (and his students like Arendt, Heidegger, Klein, and Koyre) saw science in a different way, and their thinking about "phenomenology" is relevant today.

Tech critique is an urgent and topical project far, far beyond the selfish labour relations of the Luddites, the angry madness of Theodore Kaczynski, or the loving comedy of Bill Hicks and George Carlin. We must not be ashamed to dive into it, and most especially encourage our fellow scientists, engineers and developers to do so.

Husserl's phenomenologists argued that instead of expanding our understanding, technology actually narrows it. We see less and less of reality and more and more of our instruments and theories. With social control media we see more and more of ourselves in the black mirror, and like Narcissus we are stuck. Our experience of being, indeed all experience is killed. The writer Max Frisch thought technology is "the knack of so arranging the world that we don't have to experience it."

If you think about your phone that's so obviously true. You want to go places and see them but instead you stare at maps or through your screen to photograph things. You want to date and feel love, but encounter extraordinary weirdness, lies and false faces in all the other "humans" (are they?) it connects you with. You seek knowledge but find paywalls, subscriptions and adverts. The whole experience of a smartphone seems to frustrate and obviate every one of its ostensible functions. You pick it up wanting to feel good and whole, and throw it down feeling doom-raped and disgusted with yourself and the world.

Of course the device itself is a miracle. It's a triumph of human achievement. All human achievement; including our dark and dangerous ones. They lurk in the design of interaction, in the network of companies and directing minds behind the device, and the sketchy provenance of the information it connects you to. They compose a hurt-locker of human frailty, jealousy, insecurity, deviousness and deviance, wired up on a one-click hair-trigger. It is a child's toy box filled with kaleidoscopes and dolls, but also sharp knives, loaded mouse-traps and poison bottles.

Why did we make such a thing?

Erich Fromm, Lewis Mumford, Neil Postman and Heidegger himself expressed the reason in slightly different ways - but the reason is that "there is no reason". "Instrumental technology" is a tool without a task. A solution looking for problems. It is a way of seeing, or framing "reality" but we don't know what we're doing with it. There is no plan. We have a vague idea that it is a "means to an end" without ever having asked what that end is.

The current version of the operating manual for technology says something like:

"Feed your technology money. Let it be. Technology that consumes and excretes more money will prosper and favour its kindred and offspring."

This is an elegant idea given some very naive assumptions;

- all technology is an unqualified good

- there are natural bounds and rate limitations

- technology does not compete with humanity

Look around the world, and please raise your hand if you think these conditions hold? This is what governments of the "west" have decided is the best way to deal with the complexity of progress. I say that it is the ultimate betrayal of reason and responsibility. A cowardly cop-out.

Technology has no essential purpose except to evolve itself. But having believed that there is an end, we then make ourselves the pliable subject of a supposed deal or bargain with technology. Things are in the saddle and ride man, says Emerson. We reify ourselves, as Fromm says, and fall (in Postman's terms) into abject submission before technology.

The irony is that all the while we believe we are powerful. We believe that the technology gives us "control". We believe we are "connected", but little do users know that their "community of folk" is an algorithmically created bubble designed top trap and feed them spew in return for advertising clicks.

Of course all this seems Faustian, but it is worse. Faust at least has a chance to "trick the devil", because he knows what he wants. Technologically bewildered man has no redemption and is on a path to nihilism and madness. It's a neurotic and restless path, forver seeking "the new", constantly shaping and reshaping the world, restructuring, tearing down, rebuilding, but without moving forwards.

In Ray Bradbury's "The Martian Chronicles" the settlers from Earth are lured to their deaths by telepathic Martians who project each settlers expectations and desires of a perfect comfort (Mars is Heaven!) which includes ressurected family members and idyls of bucolic American life. Mind control is always more effective with carrots than sticks. As a narcotic for deceptive psycops, technology is a tool, or weapon, which if we allow it to be wielded by the bewildered, the selfish and deceitful rather than the wise and open, will serve all of humanity very badly.

Technologists are therefore not the wisest or best people to decide about the biiger picture of how technology should be used. On the contrary, most of us computer scientists lack elementary political and cultural sense. Like his cohorts in the US today, Elon Musk and the other "tech bro" wannabe "leaders" lack essential humility and humanity.

Where do we start on the road to responsibility?

Devaluing of the arts and humanities, particularly history, literature and philosophy - essential as a balance for human-centric tech progress - is something we must correct. For most of history our moral schisms appeared around military technology. In a classic comment by Mikhail Kalashnikov and the recent film adaptation of J. Robert Oppenheimer's life we see the ancient tension at play.

In the 1930s Huxley anticipated the pharmaceutical dimensions of violence. But things got much more muddied in the last 20 years. Many technologies assumed to be socially good for their "connecting" value, or at least nominally neutral, have turned out to be very problematic. For example; "social media" has effectively destroyed the social. It may have destroyed democracy. This accompanies a militarisation of civil space since the Internet, originally a DARPA project, inducted many of its values silently into everyday life.

On top of that, as business ran out of new things to do and make, they shifted toward a cannibalistic culture of "surveillance capitalism", antithetical to democracy, which has weaponised practically all digital technology against the people and lent tacit approval to the violation of privacy for profit. Runaway compound effects have made people with control of digital systems able to gather even more power to shape the direction of development to their favour.

It is therefore against this background of technology not just as an enabling tool - but a powerful weapon aimed against all of us - that we must consider rights and responsibilities.