Roughly half of the labor force of most major technology companies consist of contingent staff; vendors, temps, contractors, etc. Despite the asterisk next to my name and an orange badge instead of a blue badge, it was still a highlight of my engineering career when I became a vendor at Microsoft. But the celebrations came to a crashing halt after being reminded by a full-time employee (FTE) that I was not paid to think, only to do as I was told as a vendor. Although I didn’t know much about management at the time, I knew that no acceptable realm of management advised the demoralization of ambitious new hires and this sort of reception perplexed me.

If this was truly the case, then Microsoft could have easily replaced my efforts with unthinking algorithms and saved the $70/hour that they were paying my vendor company for my time; not that I saw all of that. They could have hired any geek off the street to do as they’re told instead of an expert in their field that I was. Whether he liked me or not, I was hired because I knew significantly more about Exchange, 3rd party messaging technologies, and the Microsoft stack than the boomer trying to belittle me, so this sort of treatment just didn’t add up as far as I was concerned.

To be fair, my initial experience could have easily been a simple case of a bully with low self-esteem trying to elevate themselves by making others feel inferior. But vendors compare notes and this experience was consistent with many contingent staff throughout Microsoft and other tech giants. This treatment seemed to be the status quo. Whether or not it was the case and even after becoming an FTE myself, this dynamic still compelled me to question the true role of vendors throughout tech for years to come.

Initially and like many others, I viewed my role at the company as a vendor functioning simply as a cost-effective trial run and a foot in the door as many temp jobs are. As far as I was aware, this was typical of temporary staffing and little else. As such, I interpreted this sort of treatment as a challenge to see how I handled adversity and opted to showcase my worthwhile letting my actions necessitate a full-time offer; a trial by fire if you will. So I worked like a velocidonkey with a blue badge for a carrot dangled in front of me in an effort to change my employment status.

Although this treatment didn’t demoralize or demotivate me in the slightest, countless others took this second-class treatment to heart. While I didn’t have much to lose and could take more risks, plenty of others had more riding on their paychecks such as their families or other dependencies. So they opted to endure the abuse, do as they were told, and maintained a low profile so as to avoid confrontations with FTEs that could end their career there in an instant; almost as if they were indentured servants or slaves.

This caste system of sorts had a crippling effect on their performance in turn. It’s difficult to be at your best when you’re perpetually worried about losing your job with few protections or recourse if you are terminated and this is especially true in a grind house of an industry like big tech. Less stress equates to more output. Because of this, I couldn’t view such a reception as a futile attempt at reverse psychology or a managerial tactic meant to identify the best candidates out of their labor force.

Given how consistent this experience was with other vendors inside and outside of my org, I eventually concluded that they not only needed vendors to think to do their job, especially since they expected our work to be of the same caliber of any FTE, but that they needed vendors to think less of themselves than that of a full-time employee as well. It became obvious that demoralizing and oppressing half of their labor force into a techno-caste while distributing them throughout countless salary sucking vendor companies served an actual purpose.

Since most of the actions of giant firms such as Microsoft are intentioned and calculated, why they did this and what purpose this dynamic served were the real questions on the top of my mind. Obviously, it was done in the pursuit of profit, but how exactly this dynamic translated into profit was still a mystery to me. One thing was for certain, it wasn’t done in the name of empowerment.

While many would like to think that their dependence on vendors was an administrative cost-savings measure as I did at first, vendors aren’t short-term staffing solutions there. Many vendors have worked in the same permatemp capacity for years. Because of this, Microsoft didn’t seem to achieve much in the realm of cost-savings from this dynamic because they paid a perpetual premium for our services designed to be short-term. Forcing vendors to take a 6 month break after an 18-month contract didn’t exactly increase cost-savings either and plenty of vendors received exemptions from this mandate.

Sure, their reliance on contingent staff limited the administrative overhead necessary to facilitate benefits for everyone and saved them from having to provide elaborate offices for us as they did for many FTEs. They didn’t have to worry about severance, unemployment insurance, FMLA, or even the health of their vendors either. But they also didn’t have to pay their full-time employees overtime like they often do with their contingent staff and the cost disparity between a vendor and an FTE was minimal and there were countless examples of vendors netting more than their FTE peers after the middlemen got their cut which ranged between 30–50%.

Vendor or FTE, there was a slow ramp-up process that could take months for them to get up to speed while losing competent vendors inflicted as much or more operational pain as losing FTEs. As such, the operational losses from turnover and attrition were mostly a wash like the supposed administrative savings. Ironically, when I eventually left my vendor role for a full-time offer, I was still retained on a part-time basis for months afterward in order to support and handoff the project that I was leaving behind.

Maintaining relationships and contracts with 100+ vendor companies wasn’t burden-free from an administrative perspective either. It may have solved one problem but it created another. As is the case with most aspects of life, increasing the middlemen in your bottom line seldom results in cost reductions. Even the most inept engineer at Microsoft can confirm that complexity inflates overhead costs. So direct cost-savings from such tedious efforts was a very hard sell in my opinion.

With all of these idiosyncrasies canceling out the stereotypical benefits associated with contingent staffing, I was still left wondering how Microsoft could benefit from distributing half of its labor force through 100+ vendor companies. After becoming an FTE, I was still left to question why they needed so many vendors, vendor companies, and this second class treatment instead of hiring them outright or at least treating them as equals. It goes without saying, but we as FTEs weren’t told to oppress and demoralize vendors or treat them as second class citizens, we just weren’t told not to nor were we disciplined if we had; at least not at my pay grade. But it still wasn’t made apparent why we maintained such an obvious caste system or relied on so many contingent staffing companies in the first place.

As one gains shares in a company though, how they evaluate public companies changes and some of the lesser understood advantages to their vendor dynamic became more apparent as time went on. One distinct advantage of this vendor dynamic could be found when looking at how publicly traded companies are evaluated by analysts. Key performance indicators (KPIs) of how efficient a company is can be found in their revenue per employee or turnover metrics among others which vendors are excluded from entirely. In doing this, they render the company much more efficient and viable in the eyes of analysts by effectively hiding half of their labor force.

Although many tech companies have a near 1:1 ratio between their employees and vendors, Google, Facebook, Amazon, and IBM included, they essentially double their efficiency on paper by burying the payroll of their vendors within various operational costs instead of reporting it like they do with their FTEs. At the time at Microsoft, it was the difference between showcasing $800,000/employee and $400,000/employee which is significant. While this may seem minuscule to the untrained eye, this is huge for analysts.

But when added to the other traditional justifications of contingent staffing, such an approach didn’t justify working with so many different firms that didn’t specialize in anything besides putting asses in seats, let alone the caste system and unnecessary complexity that this dynamic seemed to foster. They could have easily accomplished this with a handful of vendor firms, but clearly needed more for some reason, hence why they had more. Jumping through all of these hoops and scraping the barrel so hard for such small ends still didn’t make complete sense.

As one might do when considering abuse and pay disparity though, I eventually began to wonder why vendors wouldn’t unionize in the face of such treatment. In turn, this line of inquiry inadvertently led me to another lesser-known but no less distinct advantage to this sort of labor distribution. When huge corporations are faced with unionization or the labor strikes that come with them, it becomes a simple matter of divide and conquer and this approach could serve as a preemptive strike against them. Corporations tend to despise the mere notion of unionization and this approach severely limited the ability of their entire labor force to bargain collectively, let alone go on strike, by driving wedges between them.

Just as you aren’t supposed to put all your eggs in one basket, they didn’t retain their workforce through a single company. While unionizing one company is incredibly difficult, unionizing 100+ companies borders on the impossible; especially in unison. With such a dynamic at play, Microsoft’s labor force perpetually scabbed itself over and had little to no ability to function as one. Even if an entire vendor company unionized and went on strike, Microsoft’s ability to maintain productivity remained intact, albeit degraded. In turn, this degraded the ability of vendors to bargain collectively and mitigated their leverage should they go on strike.

If one vendor company unionized, it’s of little consequence to Microsoft because the vendor company had to eat the added costs associated with unionization. Without specialty and while simply putting asses in seats, these vendor companies could easily be replaced by another non-union shop. And when it eventually became time for a would-be union vendor company to renegotiate their contract with Microsoft, they could simply pull that contract and award it to another non-union vendor company that could offer the same services for less. Unionization was effectively a death sentence from the perspective of a contingent staffing firm, not to mention a guarantee that you would probably not get hired into a full-time position for aspiring vendors.

Conversely and if their FTEs unionized and went on strike, Microsoft could depend on their vendors to function as scabs and work as a skeleton crew to maintain some semblance of productivity. It wouldn’t have been perfect, but vendors do the lion’s share of the labor at Microsoft which enabled them to maintain productivity and minimize the impact of a would-be FTE strike just the same. Seemingly, the vendor dynamic that these companies tend to create seemed to function as a shelter from unions and strikes more so than simple payroll or administrative cost-savings.

After all, labor strikes are harmless if their collective absence doesn’t hinder productivity severely and these practices effectively hardened Microsoft against productivity loss resulting from potential strikes. Similar to dodging taxes through various shell companies, it seemed as if Microsoft and the rest of these major tech firms were protecting themselves from unionization and potential strikes by treating vendor companies as organized labor shelters. Despite the obvious ethical misgivings, where many see anything from myopic ignorance and complexity to a bureaucratic nightmare, I finally saw genius in these tactics.

With this in mind, the caste system of contingent staff made much more sense as well. It wasn’t about cost-savings so much as it was about division, oppression, and dominance. From sugar cane and banana farmers to software engineers, the same rules seem to apply to us all.

Even their fervency for H-1B hires made much more sense from this vantage point as these types of had significantly more to lose than a normal vendor while diversifying their labor force even further and commanding a fraction of the salary of FTEs. While FTEs and vendors stood to lose their job, H-1B workers might lose their ability to live in this country if they acted out of line. So many opted to keep a low profile like a vendor.

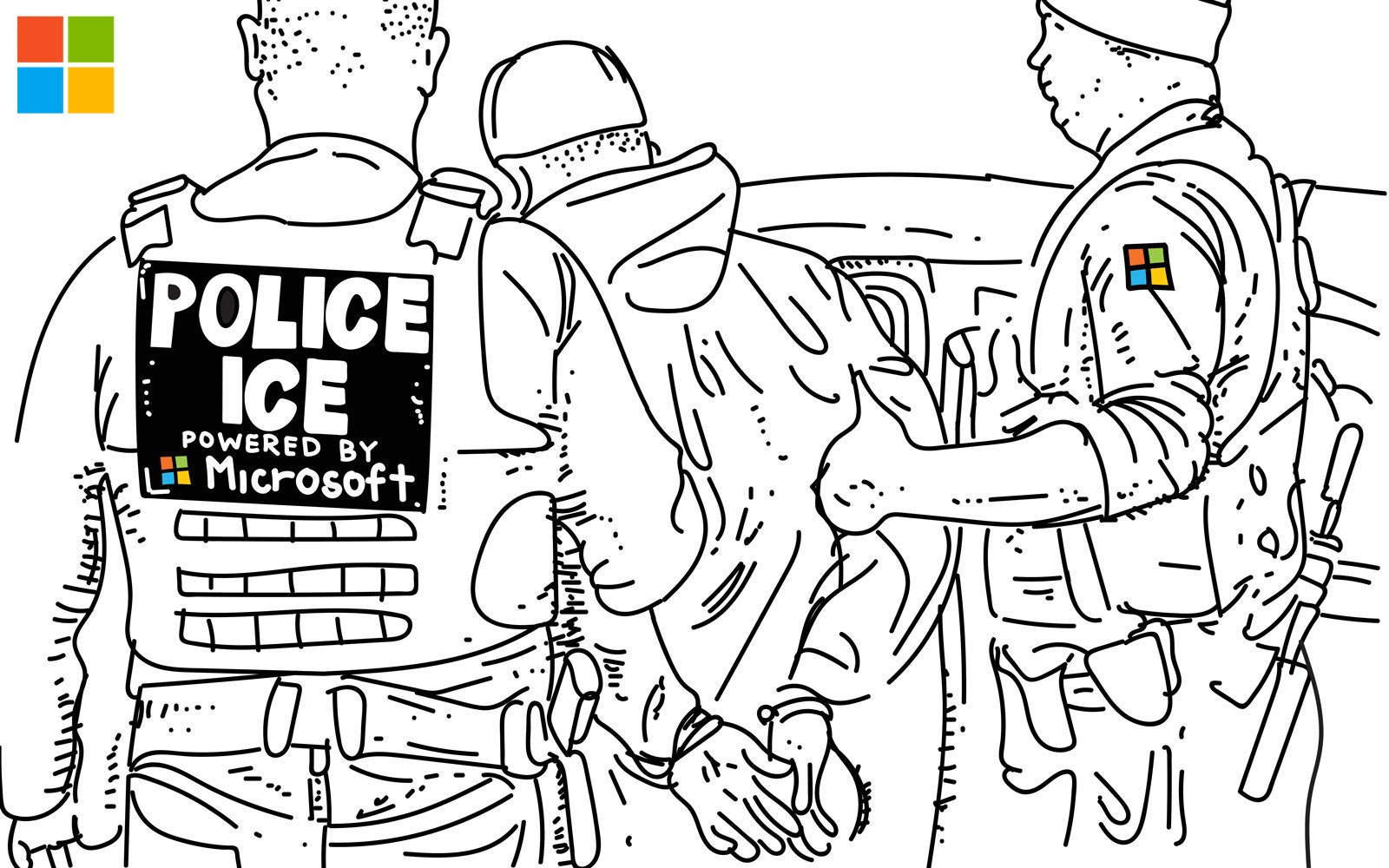

Even their penchant for hiring white male right-wingers throughout their full-time ranks made much more sense; especially management. Such demographics tend to vehemently oppose unionization while also being much more tolerant of nationalist causes. In turn, this naturally renders their FTEs less likely to dissent and question authority, let alone consider unionization or a strike as a whole. This appeared to be why so many FTEs blindly tow the company line while taking no exception to their cooperation with the likes of ICE, CBP, and the DOD.

In summary and although technology companies are beginning to receive flack for union-busting when employees begin to make a stand, large corporations seldom get the credit that they deserve for the efforts made to prevent such stands from being made. Although this is not the intended purpose of contingent staffing, in excess it can function as an organized labor shelter. The second-class treatment and oppression merely reinforce this dynamic while the administrative cost-savings filched from these practices and how they look to investment analysts are merely the gravy on top.

Disempowered, divided, and demoralized labor forces are far less likely to realize their true worth, let alone unite, stick their necks out, and demand fair treatment regardless of their employment status. FTEs are on the losing end of this dynamic just the same. If major tech companies have to bust unions the good ol’ fashion way, then they’ve failed. Instead, they seem to strategically organize themselves in a manner that enables them to mitigate the discussion of unions from ever happening in the first place. ⬆