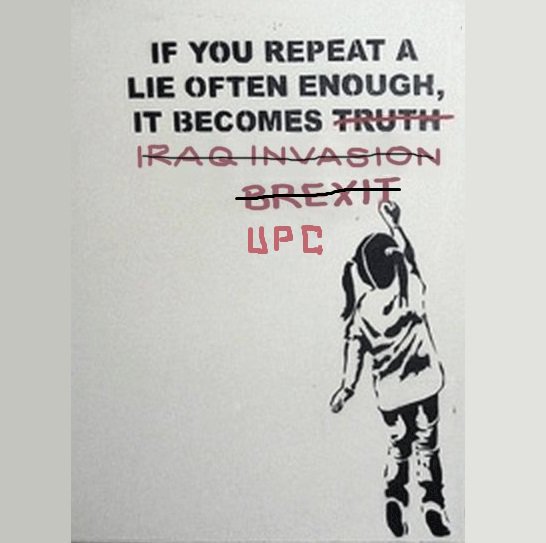

And that brings me to patents. As everyone in the IP market knows, over recent year Europe has emerged as a much more important part of the equation for patent owners seeking to assert their rights. For multiple reasons – including the perceived quality of EPO-granted assets, speed to get a decision, the relatively low cost of litigating, the expertise of courts and, crucially, the availability of injunctions – the worsening environment for rights holders in the US is driving more companies to try courts in Germany, the UK and other European jurisdictions. Should the Unified Patent Court ever become a reality that process is likely to accelerate.

[...]

Where that leaves lobbying efforts that seek to water down or eliminate the UPC injunction regime, for example, remains to be seen. My guess is that as long as BigTech identifiably campaigns as BigTech it is unlikely to get much traction. Instead, what it needs are examples of small European companies falling foul of abusive patent litigants – the kinds of stories that it has always been possible to dig out in the US. The problem is that in Europe these are tough to find – precisely because the system is not troll-friendly. Getting around that may be a challenge that even the expertise of Silicon Valley’s best paid public relations advisers and lobbyists will struggle to meet.

If it is not an EU institution, then I do not understand why in the the preamble of the UPCA the following is said:

RECALLING the primacy of Union law, which includes the TEU, the TFEU, the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, the general principles of Union law as developed by the Court of Justice of the European Union, and in particular the right to an effective remedy before a tribunal and a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal, the case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union and secondary Union law;

Furthermore Art 1 of the UPCA states: The Unified Patent Court shall be a court common to the Contracting Member States and thus subject to the same obligations under Union law as any national court of the Contracting Member States.

If I understand well, the TEU and TFEU should thus be clearly applicable. Or did I miss something?

Divisions of the UPC can bring forward prejudicial questions to the CJEU, but the the text governing the UPCA cannot be submitted to the CJEU. I fail to understand the logic behind such a position.

Could somebody explain.

It’s not that hard to understand, given the limits of the jurisdiction of the CJEU.

In essence, the CJEU can only review the legality of EU Treaties and the (legislative) acts of EU bodies. The UPCA is not an EU Treaty or legislative act, as it is instead an international agreement (that just so happens to be exclusively between EU Member States).

However, this is not to say that the CJEU will have no teeth when it comes to the effects of the UPCA. That is, pursuant to Article 258 or 259 TFEU, the CJEU will be able to assess whether the Member States that are party to the UPCA are fulfilling their obligations under the EU Treaties. Unfortunately for the public, however, such actions can only be commenced either by the Commission or another Member State.

This effectively means that a challenge by Spain (under Article 259 TFEU) might be the only hope of sorting out whether the actions of the UPC (or the Participating Member States) are compliant with EU law.

It remains to be seen which grounds could be raised by Spain under Article 259 TFEU. However, Article 118 (attributing the European Union with exclusivity regarding the creation of uniform IP rights) is an interesting possibility.

In C-146/13, the CJEU held that:

“Notwithstanding the fact that the contested regulation contains no list of the acts against which an EPUE provides protection, that protection remains uniform in so far as, regardless of the precise extent of the substantive protection conferred by an EPUE by virtue of the national law which is applicable, under Article 7 of the contested regulation, that protection will apply, for that EPUE, in the territory of all the participating Member States in which that patent has unitary effect”.

In other words, the CJEU held that Art. 118 TFEU was not contravened because EU law (the UP Regulation) has been used to achieve (partial) harmonisation, through the designation of a single, national law.

However, this would appear to mean that failure of the UPC to apply a single, national law (as determined under Art. 7 of the UP Regulation) would therefore not only contravene the Member States’ obligations under the UP Regulation but also their obligations under Art. 118 TFEU.

This puts an interesting “spin” on the law of infringement to be used under the UPP, doesn’t it?

For a start, it would appear that the UPC would only be able to refer to the infringement provisions in the UPCA to the extent that those provisions are fully incorporated into the national law selected under Arts. 5(3) and 7 of the UP Regulation. This means that the UPC, as well as all patent attorneys, will need to become experts on the extent to which this is true in each of the relevant Member States... and also what the significance might be of seemingly contradictory / non-identical provisions in national laws.

On the other hand, it would also seem to force the UPC to issue judgements for “traditional” (not opted out) EPs on a country-by-country basis. This is because the UP Regulation does not contain any provisions on the law to be applied to “traditional” EPs... meaning that there is no basis under EU law for the law of infringement for those EPs to be “harmonised”. Also, attempts by the Member States to “go it alone” with harmonisation of the law with respect to such EPs may well contravene the provisions of Art. 118 TFEU.

To put it another way, as the UPCA is not part of EU law, how can the provisions of that Agreement be used to “harmonise” patent law (for UPs or not opted out EPs) within the EU without infringing Art. 118 TFEU?

Alternatively, Spain could think about a further challenge the legality of Regulation 1257/2012.

As previously mentioned, the impermissible, retroactive effect of Article 5(3) might be one ground for such a challenge. This is because that Article applies new / different laws (of infringement) to pre-existing patents and patent applications, as well as to acts committed prior to entry into force of the UPP. That hardly seems compliant with the principle of legitimate expectations!

Another, very interesting possibility might be alleged contravention of Article 18 TFEU (“any discrimination on grounds of nationality shall be prohibited”) by Article 5(3) of the UP Regulation.

Understanding this ground requires a little thought.

Firstly, Art. 5(3) states that the applicable law of infringement is determined by Art. 7. Secondly, the primary factor to be considered under Art. 7(1)(a) is residence / place of business. For many individual and corporate applicants, their residence / place of business will be the same as (ie equivalent to, or a surrogate for) their nationality.

Thus, the UP Regulation requires the selection of a single, national law based upon a criterion that, for many applicants, will be a surrogate for their nationality.

The final step is to realise that the national laws of infringement are not harmonised. Thus, inventors / applicants that have identical claims, but that have different nationalities, would have different laws of infringement applied to those claims (and hence potentially different results from litigation).

It really is hard to understand how this could possibly be compliant with Article 18 TFEU!

If it is an EU institution why would it need its own dedicated Protocol on Privileges and Immunities ? Surely it would be covered by the EU PPI ?

We are ahead of interesting times, and it might be possible that the CJEU considers the UPCA not in accordance with EU law. In view of the sometimes political nature of the CJEU's decisions, I doubt that it would blow up the whole system, but it could severely harm it.

In the same vein, there is a further question which could be tricky as well. If an opposition is launched against a UP, can the opposition division be composed of nationals of non EU member states?

This becomes particularly critical if the EP has only been validated as a UP.

One could consider that since the EPO regains competence by virtue of an opposition, then the composition of the OD is irrelevant.

On the other hand, one could also consider that having become, at least in some member states of the EPC which are also members of the UPC, an asset according to EU law, its fate can only be decided by nationals of member states of the EU.

If the patent is revoked, then there is no revision possible. And here we are back to the other complaints before the German Constitutional Court.

This question was raised at the latest conference on the UPC in July in Munich, and has up to now not received a reply.

"the sometimes political nature of the CJEU decisions"? Are you suggesting that the CJEU might not demonstrate complete independence from the executives of the Member States and/or the executive arms of the EU?

If there is a (perception of) lack of independence, then perhaps it is high time that someone took a close look at the conditions of appointment of the judges of the CJEU, in order to see how well the CJEU fares regarding internationally recognised "best practice" for achieving judicial independence. ;-)

I do not want to claim that all decisions of the CJEU are more of political than strictly judicial nature. It is a minority of decisions, but the manner in which the CJEU has dismissed the second complaint of Spain against the UPC is an example to me of more political decisions.

Any reason not to consider Spain's complaint were good to dismiss the claims. Some of the questions were however quite specific.

In decisions on the correct application of directives it is certainly not politic. Plenty of those have been published and commented on this blog.