Online anonymity seems to have come under attack by sites that attribute it to "trolls" or vandals. In addition, all sorts of pro-surveillance circles would like us to think that when someone pursues online anonymity, then he or she is up to no good. The EFF has just published a good article [1] which gives examples of when online anonymity is absolutely crucial, not just desirable. Here is the list of hypothetical scenarios:

- the people who run some of the funniest parody Twitter accounts, such as @FeministHulk (SMASH THE PATRIARCHY!) or @BPGlobalPr during the Deepwater Horizon aftermath. San Francisco would not be better off if we knew who was behind @KarltheFog, the most charming personification of a major city's climate phenomenon.

- the young LGBTQ youth seeking advice online about coming out to their parents.

- the marijuana grower who needs to ask questions on an online message board about lamps and fertilizer or complying with state law, without publicly admitting to committing a federal offense.

- the medical patient seeking advice from other patients in coping with a chronic disease, whether it's alopecia, irritable bowel syndrome, cancer or a sexually transmitted infection.

- the online dater, who wants to meet new people but only reveal her identities after she's determined that potential dates are not creeps.

- the business that wants no-pulled-punches feedback from its customers.

- the World of Warcraft player, or any other MMOG gamer, who only wants to engage with other players in character.

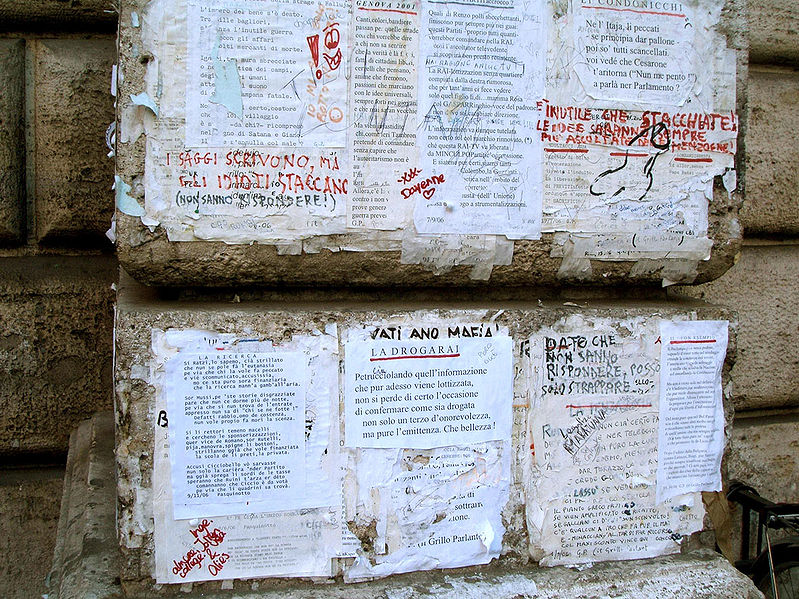

- artists. Anonymity is integral to the work of The Yes Men, Banksy and Keizer.

- the low-income neighborhood resident who wants to comment on an article about gang violence in her community, without incurring retribution in the form of spray paint and broken windows.

- the boyfriend who doesn’t want his girlfriend to know he’s posing questions on a forum about how to pick out a wedding ring and propose. On the other end: Anonymity is important to anyone seeking advice about divorce attorneys online.

- the youth from an orthodox religion who secretly posts reviews on hip hop albums or R-rated movies.

- the young, pregnant woman who is seeking out advice on reproductive health services.

- the person seeking mental health support from an online community. There's a reason that support groups so often end their names with “Anonymous.”

- the job seeker, in pursuit of cover letter and resume advice in a business blogger's comments, who doesn't want his current employer to know he is looking for work.

- many people's sexual lives, whether they're discussing online erotica or arranging kink meet-ups.

- Political Gabfest listeners. Each week, the hosts encourage listeners to post comments. Of the 262 largely positive customer reviews on iTunes, only a handful see value in using their real names.

During last week's episode of Slate's Political Gabfest, a weekly podcast I normally adore, senior editor Emily Bazelon mocked the concept of online anonymity. Our society would be better off if everyone was forced to put their name to their words, she said, generalizing that online anonymous users are poisoning civil discourse with their largely vile and defamatory comments. She deemed only one class of user legitimately deserving of anonymity: "people who directly fear violence."

In this view of the Internet, everyone else's anonymity is worth sacrificing to silence the trolls.

It's easy to understand why some in the press have this perspective. If you work in online media, the bulk of your interactions involve news stories, which seem to draw the ugliest forms of discourse. If you're a public figure, you're faced with haters on Twitter who are obsessed with enumerating all the ways you suck. They're even worse in the comments on YouTube. A website, such as Slate, certainly has the right to determine the culture of its online community, and I don't have a position whether such sites, across the spectrum, should or should not allow anonymous comments, or even allow comments at all. I do, however, dispute this narrow vision of the Internet.

Many of these supporters are just jumping on a bandwagon, or have been misled about the nature of a purported dispute. Exactly why we are so quick to rush to judgement online, and to dehumanise the subject of our ire, is worth looking into further. But regardless of the reasons, the resulting mob greatly amplifies the effect on the target.