THE EPO has been using buzzwords like "fourth industrial revolution" and "artificial intelligence" lately. We have already explained why we believe these to be loopholes for software patents, among other things. IAM has just published (in its new issue) another piece with buzzwords in the headline ("intellectual property and artificial intelligence"), but we were rather surprised to then find out that even a crooked tyrant, Benoît Battistelli, became a contributor/writer for IAM. He promotes the "fourth industrial revolution" buzzwords right from the get-go (headline).

"We also quite like Professor Bessen, Lemley and others who strive to improve the patent system and take nothing for granted; if only someone like them was to run the EPO; instead we have another President coming (in less than 5 months) who's a banker."The use of buzzwords is to be expected from lawyers, politicians and marketing people; not from scientists (which Battistelli cannot understand or relate to). Software patents will occupy the remainder of today's coverage. We're still seeing new evidence that the USPTO grants these. There's no reason to do so when US courts repeatedly reject them and so do software professionals, but who's to say that policy is based on evidence or rationale?

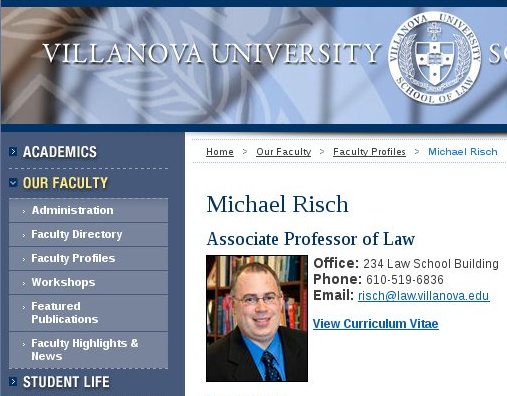

In Twitter, Prefessor Michael Risch has just announced the publication of his latest paper in which he argues that the US is doing it wrong and things "fail any economic justification." Risch studied patent trolls a long time ago. He wrote a lot about patent trolls, software patents, roots of patents in the US, patent scope, and so on. We mentioned him many times before and we don't always agree with him (especially not on software patents), but at least he's genuine and honest, unlike Battistelli.

From his latest abstract:

Though reasonable royalty damages are ubiquitous in patent litigation, they are only one-hundred years old. But in that time they have become deeply misunderstood. This Article returns to the development and origins of reasonable royalties, exploring both why and how courts originally assessed them.

It then turns a harsh eye toward all that we think we know about reasonable royalties. No current belief is safe from criticism, from easy targets such as the 25% “rule of thumb” to fundamental dogma such as the hypothetical negotiation. In short, the Article concludes that we are doing it wrong, and have been for some time.