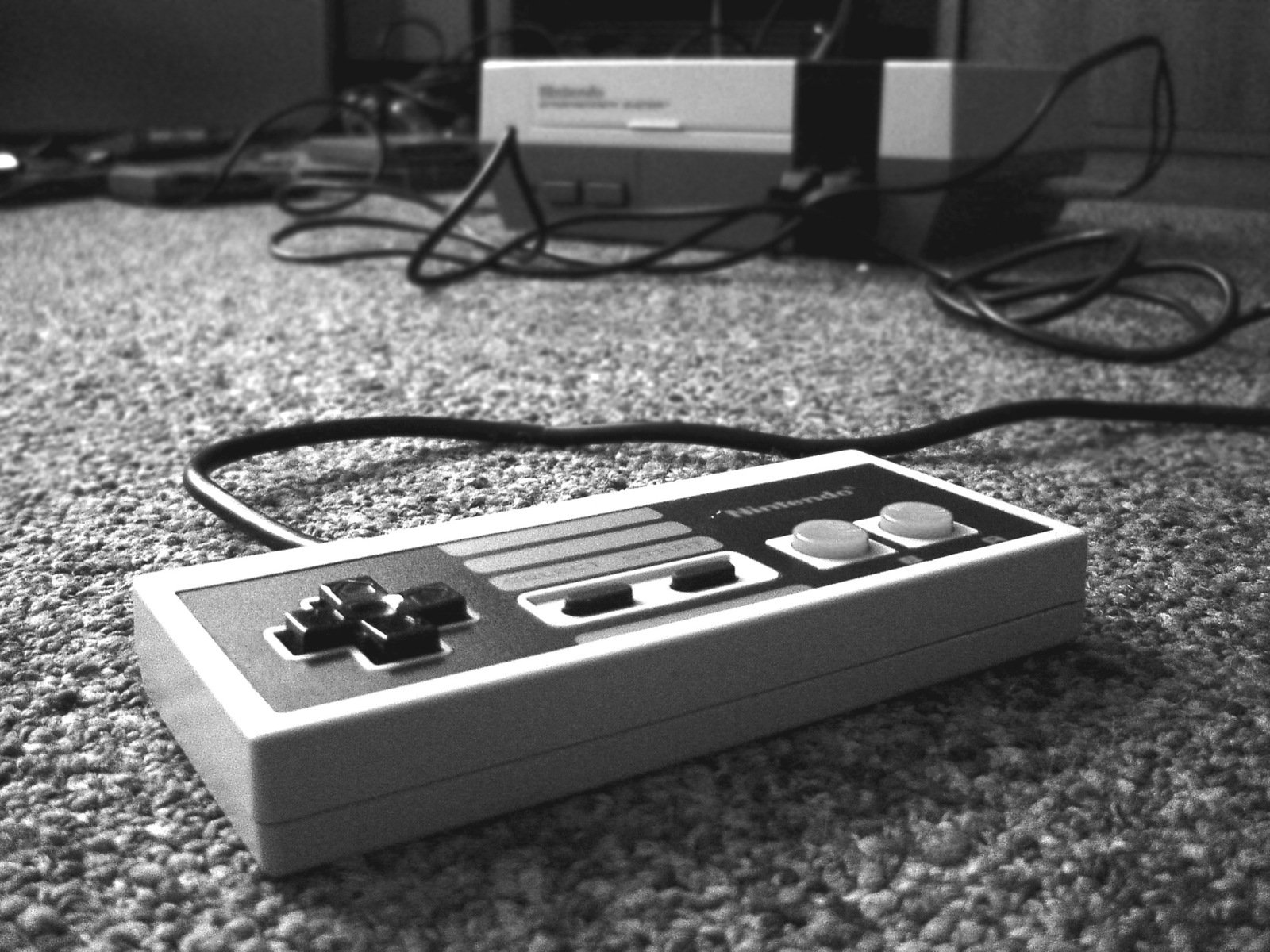

THE Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC), unlike the USPTO, rejected software patents pretty much every time last year. We watched these things very closely and back in April we wrote that "RecogniCorp v Nintendo (CAFC Case) is Another Nail in the Coffin of Software Patents in the United States".

In Mastermine, the Court considered the extent to which user-initiated methodology of a Customer Relations Management (CRM) system may be recited in system claims. The district court found certain claims of the patents-in-suit (7,945,850 & 8,429,518), indefinite for improperly claiming two different subject-matter classes citing IPXL Holdings, L.L.C. v. Amazon.com, Inc., 430 F.3d 1377( here). The Federal Circuit reversed.

In its reversal, the Federal Circuit provided helpful guidance to patent prosecutors on how to claim user-driven hardware features in the first instance, as well as how to impress upon a patent examiner that functional language of such claims does not cross the line to reciting a separate statutory class.

On appeal Microsoft challenged the Board’s standard of review. The Federal Circuit reiterated that anticipation is a question of fact subject to substantial evidence review, that ultimate claim construction and claim construction relying solely on intrinsic evidence is subject to de novo review, and subsidiary factual findings based on extrinsic evidence are reviewed for substantial evidence.

[...]

Judge Newman dissented with the majority’s finding that the Kenoyer reference neither anticipated nor obviated the ‘182 patent. After performing a clause-by-clause review of claim 6, she argued that Figure 1 of Kenoyer discloses all of the elements of claim 6 and, thus, anticipates claim 6.

Further and in opposition to the majority’s view that Kenoyer presents “multiple, distinct teachings that the artisan might somehow combine to achieve the claimed invention,” she argued that the Kenoyer reference explicitly combines the limitations to provide the same conferencing system as in claim 6. Finally, she argued that the majority’s statement that “Microsoft fails to explain how a computer, especially the computer in Kenoyer, would receive broadcast, cable, or satellite television signals” was baseless because Biscotti does not provide an explanation and both Kenoyer and the ‘182 patent treat such signals as known technology.