09.22.15

Dutch Politician John Kerstens Says EPO Investigative Unit is Called ‘the Gestapo’

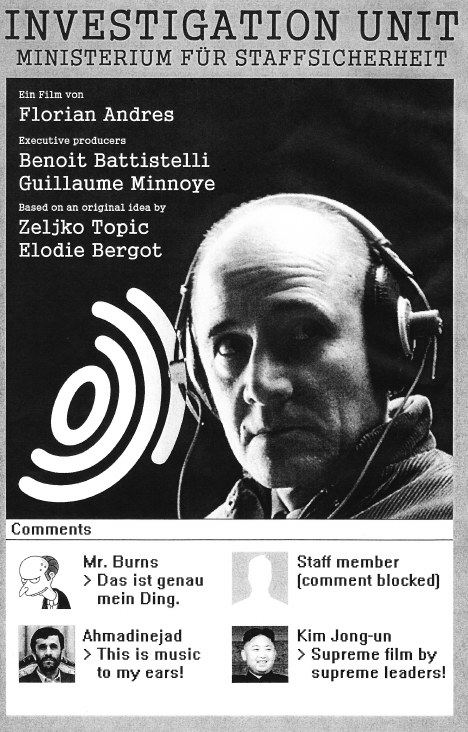

Summary: The infamous Investigation Unit (I.U.), which secretly bullies staff of the EPO with notorious interrogation techniques under virtually no oversight, is described on Dutch radio

NPO Radio 1 covered the EPO scandals 12 days ago. Several people who are aware of what is happening spoke about the subject and several days later SUEPO covered it, as its lawyer too was on the show. To quote SUEPO, “Ms Liesbeth Zegveld, SUEPO lawyer and Mr John Kerstens, Member of the Dutch House of Parliament (Tweede Kamer PvdA) were interviewed on 10 September 2015 on the Dutch channel Radio 1 over the “unhealthy working environment” in the European Patent Office.

“The audio interview is hosted here (archive).”

To quote the English part of the transcript (local copy just in case of yet another censorship induced by threats):

English translation

NPO Radio 1

“Unhealthy working environment in the European Patent Office in Rijswijk”

Eric Corton:

But first: the European Patent Office in Rijswijk.

Jingle: De Nieuws BV

Willemijn Veenhoven: Once again, an employee of the European Patent Office has committed suicide. The 42-year-old man ended

his life on the last day of his summer holidays. The EPO staff union, SUEPO, blames the “unhealthy working environment” for contributing to the fifth EPO employee suicide in three years.EC:

Liesbeth Zegveld, good afternoon. You are SUEPO’s lawyer.

Liesbeth Zegveld:

Good afternoon.

EC:

You represent the union’s members. Can you tell me about the EPO and what is happening in Rijswijk?

LZ:

EPO is an international organisation with offices in five countries, the largest of which are located in Munich, Germany and Rijswijk, The Netherlands. In total, EPO employs about 7,000 people, 50 percent of whom are represented by the staff union. Their job is to approve patent applications, which is a rather specific line of work. They have found themselves under the regime of Mr Battistelli, a Frenchman. The working conditions and the atmosphere at EPO have been extremely unpleasant for years now. Even after a considerable amount of legal action, they have not improved. What I am seeing, and what the union is seeing, is that things are actually getting worse.

EC:

So this is not a Dutch organisation. It is a European organisation, located in The Netherlands. Could you give me an example of the working conditions?

LZ:

One of the most important problems is that the staff is not involved in the making of changes that affect them directly. Take for instance decisions regarding pensions or sick leave: these are things that affect them personally. These people are bypassed, and that is a big problem. Another problem is the extremely heavy workload. As a result of cutbacks, the pressure caused by the daily amount of work to be done is only increasing. The staff suffer from this, and they do not have a way to speak up about it or discuss it with one another. Obviously, this is detrimental to the working environment.

EC:

SUEPO sees a direct correlation between the workload and the five staff suicides over the last three years. Is there any way this conclusion could be proved?

LZ:

So far, there have been two suicides at Rijswijk. One of these people committed suicide during working hours. I don’t know if there have been inquiries into whether these suicides were related to the working climate, including the latter one. The point the staff union is trying to make is that the atmosphere at work is so hostile and the number of suicides among staff so high that it’s time for EPO to find out whether there is a correlation. That is what the management has been repeatedly urged to do, which they have declined.

EC:

They aren’t about to do that. So the president… I’m sorry, go on.

LZ:

“So far, there have been two suicides at Rijswijk. One of these people committed suicide during working hours.”

–Liesbeth ZegveldThe Labour Inspectorate will try to visit the office to have a look at the working environment, but they are kept out because the EPO is a European organisation. This way, any and all questions to the EPO are met with silence. Meanwhile, the question remains: Are the suicides and the working conditions related? I do stress that this relationship has not been proved.WV:

What I am thinking right now is that people’s working conditions have to be dreadfully, but dreadfully hostile for them to resort to suicide. You are very familiar with this case: Can you imagine that the working environment really is that toxic?

EC:

For people to take such measures?

LZ:

I don’t know the case of the man who recently committed suicide. What I do know is that the atmosphere is unbearably hostile. I can confirm that. As lawyers, we try to aid and assist the staff and the workers in legal matters. This is the first time I am confronted with the limits of legal proceedings. Something has to happen right now, because the situation at these offices is getting out of hand. I’ve gotten an extremely clear sense of that. An example of this is that the EPO created an internal Investigative Unit to interrogate and investigate individual workers’ behaviour. This Unit was initially created in 2013 to have only five members and carry out investigations into severe cases of sexual harassment and fraud. So far, there have been 71 investigations in 2015. A considerable number of those were aimed at staff union members. People are put under investigation, which they are not allowed to discuss. A rather bizarre fact, as this type of confidentiality is mostly meant to protect the person under investigation, but they can’t even talk about it themselves. They cannot go public about this. These proceedings make people feel extremely intimidated. They run the risk of being fired, or if they have already retired, of getting a one-third cut off their pension. There are a lot of these investigations going on right now, a few of which I am involved in. They are baseless investigations that involve employees being asked for an interview without being told what they are being accused of and without being given any documents relevant to the investigation. These employees are confronted with all of this, a report is drawn up, and that report goes straight to Mr. Battistelli. The employee is left to await their fate, which may well be termination.

EC:

So the President, Mr. Battistelli, is deaf to any criticism. He considers complaints about the workload as nothing more than propaganda. But we have staff unions, we have the Labour Inspectorate, we have great lawyers like you. How does this organisation manage to keep you all locked out?

LZ:

Again, the EPO is an international organisation. Their offices are not just in Rijswijk, but also in Munich, Vienna and two other countries. This type of organisation’s physical premises are not part of the country they are in. The Netherlands office, for instance, is in Rijswijk, but is outside Dutch jurisdiction.

EC:

They’re not part of The Netherlands.

LZ:

“But wouldn’t that mean that a company from India or wherever could have an office in The Netherlands, abuse their employees and be exempt from Dutch law? Why are they immune?”

–Eric CortonRight. That means Dutch law, Dutch judges and the Dutch Labour Inspectorate have no authority over this office.EC:

But wouldn’t that mean that a company from India or wherever could have an office in The Netherlands, abuse their employees and be exempt from Dutch law? Why are they immune?

LZ:

These aren’t national organisations that were started in a different country but have foreign offices in several countries. These organisations are intergovernmental and have been founded by several states. So if The Netherlands, Germany, Austria and Belgium decide to found such an organisation, there is no judge that can have authority over it – only the organisation itself, or an international court of law. Of course, a self-governing organisation must govern itself correctly. And this is what we keep telling The Netherlands: every country washes its hands of it, and Battistelli is free to do as he pleases. But it’s an international organisation, so they have to take care of it themselves. Then when it gets out of hand, the International Court in The Hague, after a case that we won gloriously, rules on February 17 of this year: ‘Battistelli does

not have the right to monitor email communication, he does not have the right to decide on the duration of strikes, he does not have the right to exclude the union from negotiations with employees. Things have to change.’ At which The Netherlands as well as the organisation itself turned a deaf ear to the Court’s ruling and continued as normal. Sadly, that is the way the judicial system works.WV:

I’m sorry to interrupt, but I would like to hear from Member of the Dutch House of Parliament John Kerstens

of the PvdA party. Good afternoon.John Kerstens:

Good afternoon.

WV:

“The English term Investigative Unit has been put in German by the staff themselves as ‘the Gestapo’.”

–John KerstensYou have previously voiced your concerns about this organisation’s working conditions to State Secretary Sharon Dijksma. What did she promise you at that point?JK:

Really, we’ve knocked on the doors of everyone in the Cabinet by now, including Minister van der Steur and Minister Asscher. Things have been less than ideal for a while now at EPO, and that is just about the greatest understatement I could make. As Ms Zegveld said, people feel intimidated and unsafe. The English term Investigative Unit has been put in German by the staff themselves as ‘the Gestapo’.

EC:

Incidentally, we have tried to talk to people at the organisation, but no one wanted to talk to us.

JK:

That’s as I would have expected. We have contacts at the European Trade Union Confederation and we are in touch with the workers themselves: It’s not that they don’t want to talk, but they don’t dare open up for fear of investigations or suspension. The Cabinet’s reaction has been twofold: They are worried about this situation, but as Ms Zegveld noted, these international organisations enjoy certain kinds of judicial immunity. Which, by the way, multinational companies do not. Earlier, the impression was given…

EC:

“So could this be related to financial gain, perhaps?”

–Willemijn VeenhovenNo, you’re right.WV:

So could this be related to financial gain, perhaps? It’s been estimated that the Dutch government profits greatly from the EPO. The Office being in the Netherlands, the country apparently makes 855 million Euros off it each year. Could that be a reason they are left to do as they want?

JK:

The Netherlands has the ambition to be a haven for international organisations, such as international courts and organisations like the EPO. But the law dictates the premises of organisations are inviolable without permission from the President. In this case, that means the Labour Inspectorate cannot enter the premises, for instance to carry out an investigation.WV:

But do you think money might be the issue here?

JK:

No, I don’t think it is. But the problem in this situation is that these external parties have to be given permission by Battistelli, who is himself a part of the conflict and as such not at all interested in cooperating with them. The Dutch Cabinet has made a number of attempts: they have discussed the issue with the governing body of the EPO, the Administrative Council, made up of representatives of all the states who founded the EPO. The Netherlands have also attempted to start a dialogue on social issues inside the organisation itself. One of the participants involved is in fact a representative of the Administrative Council. But not much is happening. We have to…

EC:

Yes, what is going to be the next step? If you’ve already spoken with Mr. van der Steur and asked Parliamentary questions of Ms. Dijksma, what’s next?

JK:

“Personally, I don’t think it’s Mr. Battistelli’s prerogative to allow or disallow the Labour Inspectorate entry into the EPO. It is the Administrative Council’s decision.”

–John KerstensI’ve asked three sets of Parliamentary questions about this issue, and we get a small step further every time. Yet, there’s no solution in sight, so we’re going to have to put on a little bit more pressure. Personally, I don’t think it’s Mr. Battistelli’s prerogative to allow or disallow the Labour Inspectorate entry into the EPO. It is the Administrative Council’s decision. If The Netherlands is liaising with the Council to solve these issues, then for my next question to the Cabinet I will be asking them to get permission from the Council to enter the EPO and at least clear some things up.EC:

Member of the Dutch House of Parliament John Kerstens of the PvdA party and Liesbeth Zegveld, SUEPO’s lawyer. Thank you both very much.

JK:

You’re welcome.

“Transcripts in English, French and German are available by scrolling through the document,” SUEPO notes, so just about everyone in Europe can read it. It’s imperative that everyone in any field of technology, which is inevitably impacted by European patents, reads this.

For those who have not been keeping abreast of this long series of articles, our Wiki is a good place to start. The EPO may, unless proven otherwise, be Europe’s most corrupt institution right now. █

Content is available under CC-BY-SA

Content is available under CC-BY-SA